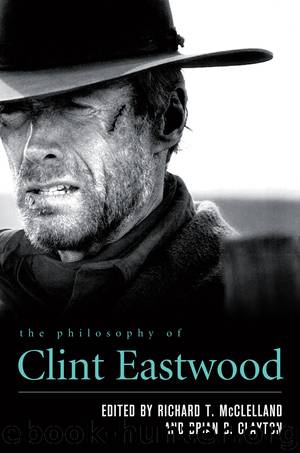

The Philosophy of Clint Eastwood by Richard T. McClelland & Brian B. Clayton

Author:Richard T. McClelland & Brian B. Clayton

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University Press of Kentucky

Published: 2014-03-20T04:00:00+00:00

GIVING UP THE GUN

Violence in the Films of Clint Eastwood

Karen D. Hoffman

The early films of Clint Eastwood’s career feature him portraying heavily armed cowboys and officers of the law who do not hesitate to use weapons to defend themselves and others. Such characters meet violence with violence and are defined by their proficiency with their guns. As Eastwood’s career unfolds, his films begin to evince more concerns about the use of violence and its impact not just on those who are on the receiving end but also on the agents wielding the weapons. In films like Unforgiven (1992), which Eastwood also directed, he depicts a character who initially appears to have rejected his violent past in favor of a life of quiet domesticity but who soon reveals that his violent past has merely been dormant. Over a decade and a half later, Eastwood directed Gran Torino (2008), a film in which he portrays Walt Kowalski, a character who is initially quick to reach for his guns but who ultimately relinquishes his weapons. Eastwood’s films, which begin with enthusiastic portrayals of gunslingers whose masculinity is understood largely in terms of self-defense, display an increasing concern about the consequences of violence and eventually culminate in a depiction of a character who asserts his masculinity even as he gives up his gun and sacrifices himself in order to save others from gang violence.1

In what follows, I discuss the shifting understanding of the proper uses and problematic abuses of violence in Eastwood’s films, particularly focusing on the gun as an instrument of violence and on the consequences of violence for the shooter. I begin by discussing the Dirty Harry films responsible for Eastwood’s association with the .44 Magnum, placing particular emphasis on the identification of the character with his gun and on Harry’s belief that the proper way to respond to violence is to wield a bigger gun. I then turn my attention to two of Eastwood’s 1970s Westerns: High Plains Drifter (1973) and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), which depict the use of the gun to avenge moral wrongs. Both films present audiences with characters who have a score to settle. But, while Eastwood’s character in the former film does not put down his gun until the fighting is over and the criminals are dead, the actions of his character in the latter film suggest that it is possible to give up the gun—at least when facing honorable men, who similarly agree to holster their weapons. Having discussed two of Eastwood’s Westerns from the 1970s, I turn my attention to a 1980s Eastwood Western: Pale Rider (1985). Here Eastwood’s character’s refusal to put down his weapon expresses a commitment to the use of the gun to defend that which is rightfully owned. Suggesting that “real” men refuse to be bullied, the film ultimately depicts the act of wielding a gun as a courageous display of masculinity.

Moving to a discussion of Eastwood’s films from the 1990s, I argue that Unforgiven takes a very different attitude toward the individual who fires the gun.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Aircraft Design of WWII: A Sketchbook by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation(32189)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31249)

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20349)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18805)

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18504)

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17637)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17314)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16933)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16881)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16599)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14493)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14319)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13952)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13467)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12954)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11708)

The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon(8855)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8788)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8767)